It poured rain most of the night. There was a small lake between us and the campsite next door when we got up. We are in this campsite for 2 nights.

We had wanted to do the historic fortress of Louisburg today but decided to wait until this afternoon. We drove to Glace Bay instead to see the Marconi National Monument, honoring the man who invented wireless communications. Read on to find out what connection Marconi had to Glace Bay.

But first I have to tell you about coal mining in Nova Scotia because, in addition to the fishing industry, this part of Cape Breton, Sydney and Glace Bay are also noted for its coal mining.

Coal mining in Nova Scotia dates back to the 17th century, making it one of the oldest mining industries in Canada, where coal deposits are abundant.

The history of coal mining in Nova Scotia is also marked by challenges and tragedies. Miners in the province have faced dangerous working conditions, including cave-ins, explosions, and health hazards such as black lung disease. The industry has experienced several mining disasters throughout its history, with the most notable being the Westray Mine disaster in 1992, which claimed the lives of 26 miners.

In recent decades, the coal mining industry in Nova Scotia has undergone significant changes due to factors such as declining coal reserves, increased environmental concerns, and a shift towards cleaner energy sources. Today, Nova Scotia’s coal mining industry has only a few operational mines remaining.

Despite its challenges, the legacy of coal mining in Nova Scotia continues to be a significant part of the province’s history and identity.

Glace Bay was originally inhabited by the Mi’kmaq people before European settlers arrived in the 18th century. The town experienced rapid growth during the 19th century due to the expansion of the coal mining industry. At its peak, Glace Bay was home to several coal mines and a bustling seaport that shipped coal to various destinations around the world.

Today, Glace Bay is a pretty little town with a beautiful coastline. We visited the monument (in the rain) and then stopped to do some shopping. By noon, the rain had pretty much gone but the wind had picked up considerably and it’s still heavily overcast.

Marconi, Wireless Communication and Glace Bay

Guglielmo Marconi was an Italian inventor and electrical engineer who is credited with pioneering long-distance radio transmission. In the late 19th century, Marconi began experimenting with wireless technology and made significant breakthroughs in the transmission of telegraph signals without the need for wires. In 1895, he successfully sent radio signals over a distance of 1.5 miles, and by 1899, he had managed to send a transmission across the English Channel.

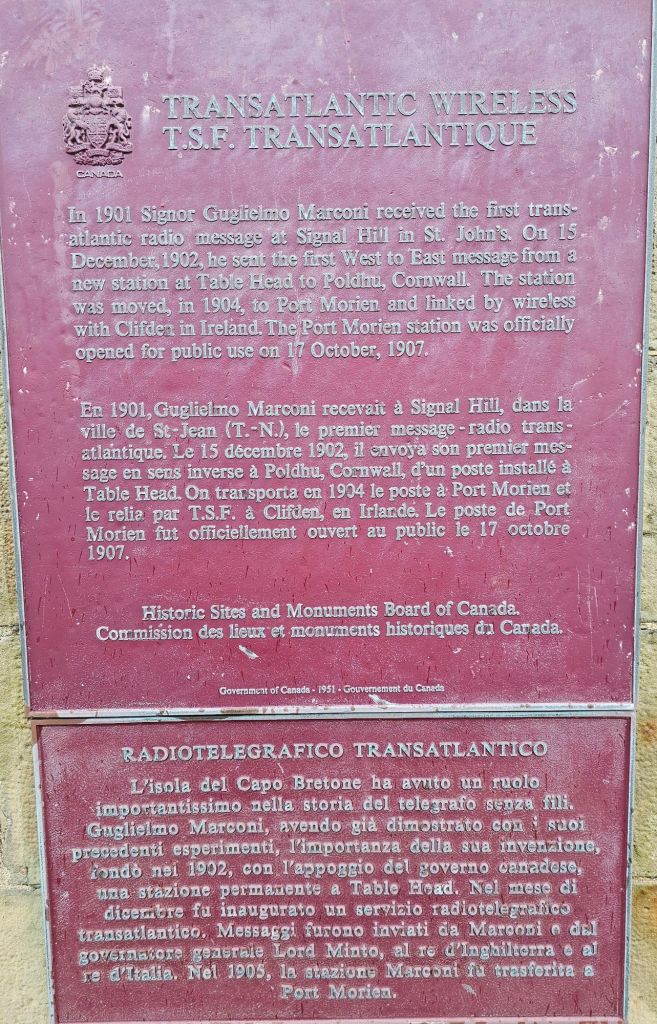

Marconi’s most famous achievement came in 1901 when he successfully transmitted a transatlantic radio signal from Poldhu, Cornwall, in England, to St. John’s, Newfoundland, in Canada. Marconi’s work in the field of wireless communication earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1909.

Late in October 1902, the Royal Italian Navy warship Carlo Alberto arrived in Sydney Harbour, arousing intense interest. Not only was the ship festooned with a bizarre array of copper aerials but on board was Signore Guglielmo Marconi, the scientific sensation of the day.

Although the Anglo-American Telegraph Company forced Marconi to end his experiments in Newfoundland ( which at that time still belonged to the UK) because it claimed he had violated its communications monopoly, Marconi immediately negotiated with Canadian Prime Minister Sir Wilfred Laurier to finance a station to be located in Cape Breton, most likely on a windy plateau thrusting out into the North Atlantic from the edge of the booming mining town of Glace Bay. Why there? Unlike his scientific contemporaries, Marconi did not labour in dusty obscurity and his Newfoundland experiences had been followed by a fascinated public, including leading citizens of Cape Breton. Marconi liked Table Head near Glace Bay, NS and on a later visit in March announced his choice of the site. The owner, the Dominion Coal Company, turned it over to him and with his financing established with support from the Canadian government, the thing was done.

By June 1905, the new station had established regular two-way daylight communication with England. So reliable dud this prove, that in February 1908, unlimited public service was inaugurated. Within a few years, all the members of the British Empire were linked by Marconi stations and indeed, in the years between the two world wars, the Marconi Company held a near monopoly of world wireless communications.

Erik Larson, Thunderstruck: “Thunderstruck” is a non-fiction book by Erik Larson that was published in 2006. The first of two narratives in the book follows the life and work of Guglielmo Marconi, the Italian inventor and pioneer of wireless telegraphy. Marconi’s groundbreaking invention revolutionized long-distance communication and had a profound impact on the world. Larson delves into Marconi’s ambitious endeavors, personal struggles, and the challenges he faced in his quest to connect people across continents.

We spent the afternoon at the Parks Canada historic site, the Fortress of Louisburg, we visited here about 30 years ago and one of our daughters set sail from here on a tall ship, so it has some personal significance, however minor.

But first we had a lovely lunch in the town of Louisburg at a lovely little bistro: tomato based salmon chowder and a beet, goat cheese and arugula salad. Just perfect.

The Fortress of Louisbourg was a significant French military stronghold strategically situated on Cape Breton Island. Constructed in the early 18th century, the fortress played a crucial role in the naval conflicts between the French and British empires in North America.

Construction of the Fortress of Louisbourg began in 1719 under the orders of the French government, in response to growing British expansion in the region and providing a key defensive position overlooking the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Over the years, the Fortress of Louisbourg grew to become one of the most formidable fortresses in North America, encompassing a vast complex of defensive walls, barracks, artillery batteries, and residential areas. The fortress served as a military garrison, a trading hub, and a center of French colonial administration in the region.

In 1745, during the War of the Austrian Succession, British forces launched a successful siege of the Fortress of Louisbourg, capturing the stronghold and dealing a significant blow to French military power in North America. However, as part of the peace treaty that ended the war, the fortress was returned to French control in 1748.

The respite was short-lived, as the Seven Years’ War (known as the French and Indian War in North America) erupted in 1756. The British once again set their sights on the Fortress of Louisbourg, launching a second siege in 1758. This time, the British forces, under the command of General Jeffrey Amherst, were able to overcome the defenses of the fortress and capture it after a fierce battle.

Following its capture, the British partially destroyed the Fortress of Louisbourg to prevent its further use as a military stronghold. The ruins of the fortress lay abandoned for many years before efforts were made to preserve and restore them as a national historic site.

Today, the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site stands as a living museum, offering a glimpse into the turbulent history of colonial North America. The site has been meticulously reconstructed to depict life in the fortress during a particular moment in time in the 18th century.

Photos of the Fortress of Louisburg

It’s off season and it also rained hard this morning. We pretty much had the place to ourselves. It was well worth the visit, not touristy, and historically accurate in keeping with its mission of honoring and maintaining a presence in the past. It took more than 20 years to accomplish. Many of the artisans were miners who had lost their jobs in the coal mines and retrained as carpenters, wood workers, stone masons, bricklayers etc. The reconstruction used the original foundations following the copious records that were uncovered on the site along with thousands of artifacts.

The reconstruction only covers 1/4 of the original fortress.

Back in camp, we had hoped we could sit outside and maybe have that campfire, but it’s supposed to rain again. Oh well. We had a good day and the rain this morning didn’t keep us from doing what we needed to do.

Tomorrow is an odd day. Brian has a board meeting for a couple of hours, I have a committee meeting for an hour or so and I would like to talk to one of my daughters.

It looks as though we will be in camp glued to our computers until after lunch and then we’ll head straight to the ferry docks. We just might get to Newfoundland yet!

You must be logged in to post a comment.