Today we are visiting the Normandy beaches used in the invasion of Normandy that began the liberation of Europe in 1944. In particular we are limiting our visit to Juno Beach where the Canadians landed ( by land, sea and air) on June 6th, 1944.

It’s a beautiful day, the best weather since we’ve been in France. We are staying in Caen, about 20 km from the beaches.

On D-Day, 6 June 1944 the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division landed on “Juno” beach in Normandy, in conjunction with allied forces. The Second World War had significant cultural, political and economic effects on Canada, including the conscription crisis in 1944 which affected unity between francophones and anglophones. The war effort strengthened the Canadian economy and furthered Canada’s global position.

The beaches we coded after the alphabetical communications code of the time. Some of them were fish, eg Gold (goldfish), Jelly (jellyfish), Sword (swordfish). Churchill felt that ‘jelly’ was too undignified for the severity of the operation and renamed ‘jelly’ to the more dignified ‘Juno’.

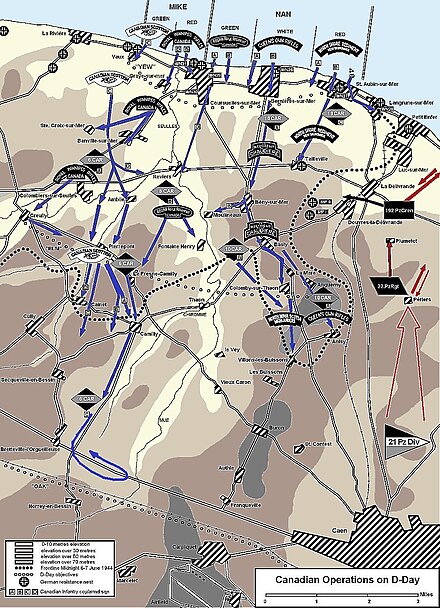

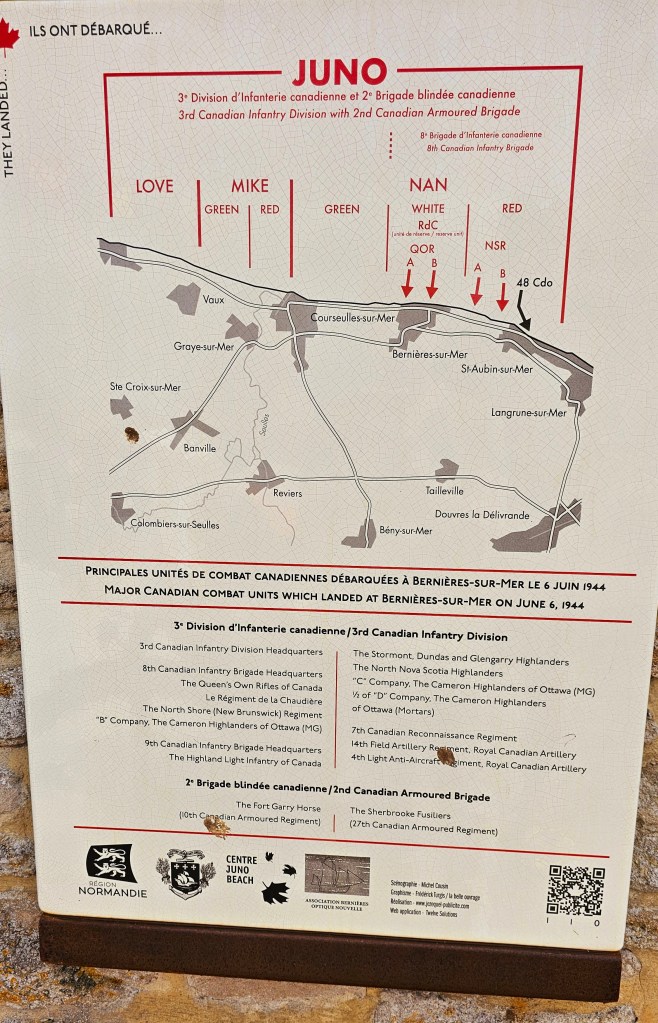

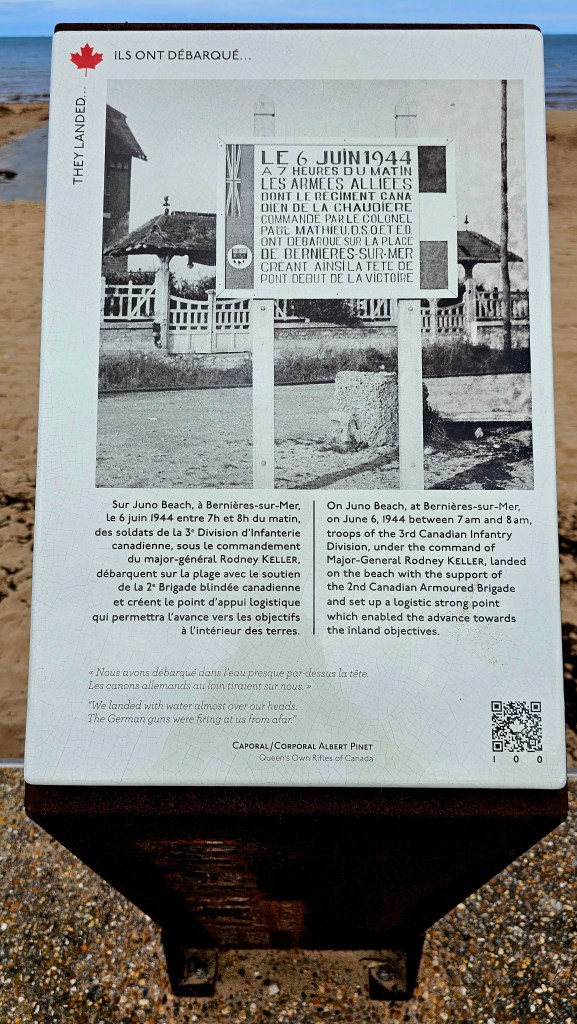

Juno or Juno Beach was one of five beaches of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France in the Normandy landings on 6 June 1944 during the Second World War. The beach spanned from Courseulles, a village just east of the British beach Gold, to Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer, and just west of the British beach Sword. Taking Juno was the responsibility of the First Canadian Army, with sea transport, mine sweeping, and a naval bombardment force provided by the Royal Canadian Navy and the British Royal Navy as well as elements from the Free French, Norwegian, and other Allied navies. The objectives of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division on D-Day were to cut the Caen-Bayeux road, seize the Carpiquet airport west of Caen, and form a link between the two British beaches on either flank. They were the only forces to succeed in their mission that day.

The beach was defended by two battalions of the German 716th Infantry Division, with elements of the 21st Panzer Division held in reserve near Caen. The Panzers were manned by a fanatical group of Hitler Youth. More about this later.

The invasion plan called for two brigades of the 3rd Canadian Division to land on two beach sectors—Mike and Nan—focusing on Courseulles, Bernières and Saint-Aubin. It was hoped that the preliminary naval and air bombardments would soften up the beach defences and destroy coastal strong points. Close support on the beaches was to be provided by amphibious tanks of the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade and specialized armoured vehicles of the 79th Armoured Division of the United Kingdom. Once the landing zones were secured, the plan called for the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade to land reserve battalions and deploy inland, the Royal Marine commandos to establish contact with the British 3rd Infantry Division on Sword and the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade to link up with the British 50th Infantry Division on Gold. The 3rd Canadian Division’s D-Day objectives were to capture Carpiquet Airfield and reach the Caen–Bayeux railway line by nightfall.

Due to heavy seas, the landing was delayed by ten minutes, to 07:45 in Mike sector and 07:55 in Nan Sector. This was at a slightly higher tide, closer to the beach obstacles and mines. The seas proved too rough to launch the DD tanks, so they were ordered to deploy from the LCTs several hundred yards out from the beach. The rising tide caused many Canadians to drown before ever reaching the beach. The landings encountered heavy resistance from the German 716th Division; the preliminary bombardment during the night proved less effective than had been hoped. Several assault companies—notably those of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles and The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada—took heavy casualties in the opening minutes of the first wave. However, strength of numbers, coordinated fire support from artillery, and armoured squadrons cleared most of the coastal defences within two hours of landing.

At the end of D-Day, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was situated firmly on Objective Line Elm, short of their final D-Day objectives. In the west, the 7th Brigade was anchored in Creully and Fresne-Camilly. The 9th Brigade was positioned a mere 3 mi (4.8 km) from Caen, the farthest inland of any Allied units on D-Day.

The German 716th Infantry Division was scattered and heavily depleted: division commander Lieutenant General Wilhelm Richter recorded that less than one full battalion could be mustered for further defence.

Despite the failure of the invaders to capture any of the final D-Day objectives, the assault on Juno is considered by some—alongside Utah—the most strategically successful of the D-Day landings. Historians suggest a variety of reasons for this success. Mark Zuehlke notes that “the Canadians ended the day ahead of either the US or British divisions despite the facts that they landed last (a delay of half an hour due to bad weather) and that only the Americans at Omaha faced more difficulty winning a toehold on the sand”. Chester Wilmot claims that the Canadian success in clearing the landing zones is attributable to the presence of amphibious DD tanks on the beaches; The DD Tanks arrival on the British beaches had been seriously disrupted by bad weather and choppy seas, and the absence of DD tanks altogether was largely responsible for the heavier casualties on Omaha, the only beach with heavier resistance than Juno. Canadian historian Terry Copp attributes the steady advance of the 7th Brigade in the afternoon to “less serious opposition” than the North Shore Regiment encountered in Tailleville.

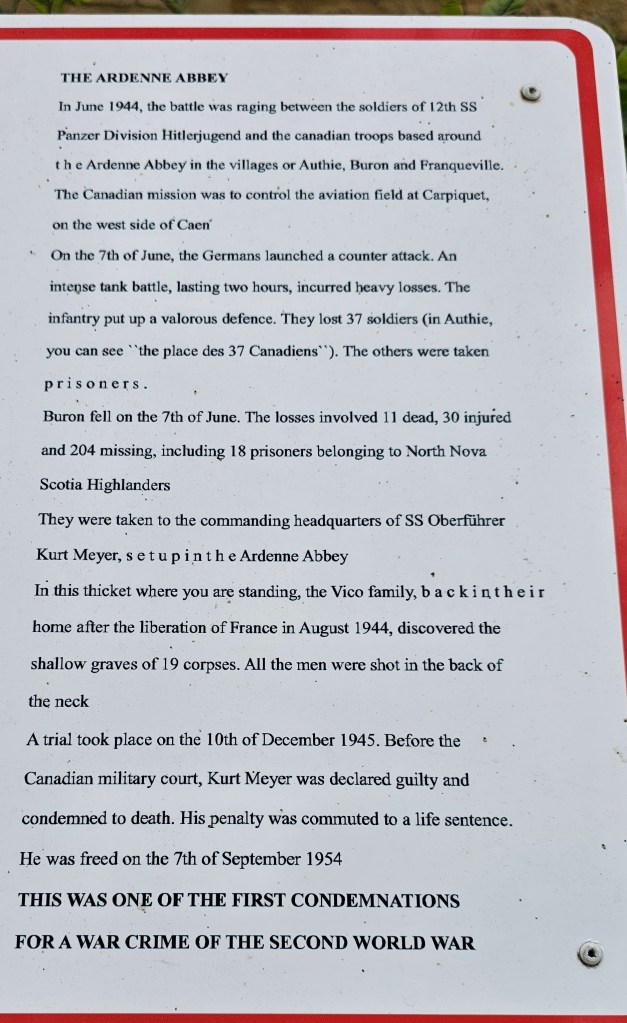

Massacre at the Abbaye d’Ardenne

The Ardenne Abbey massacre occurred during the Battle of Normandy at the Ardenne Abbey, a Premonstratensian monastery in Saint-Germain-la-Blanche-Herbe, near Caen, France. In June 1944, 20 Canadian soldiers were massacred in a garden at the abbey by members of the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend over the course of several days and weeks. This was part of the Normandy Massacres, a series of scattered killings during which up to 156 Canadian prisoners of war were murdered by soldiers of the 12th SS Panzer Division during the Battle of Normandy. The perpetrators of the massacre, members of the 12th SS Panzer Division, were known for their fanaticism, the majority having been drawn from the Hitlerjugend or Hitler Youth.

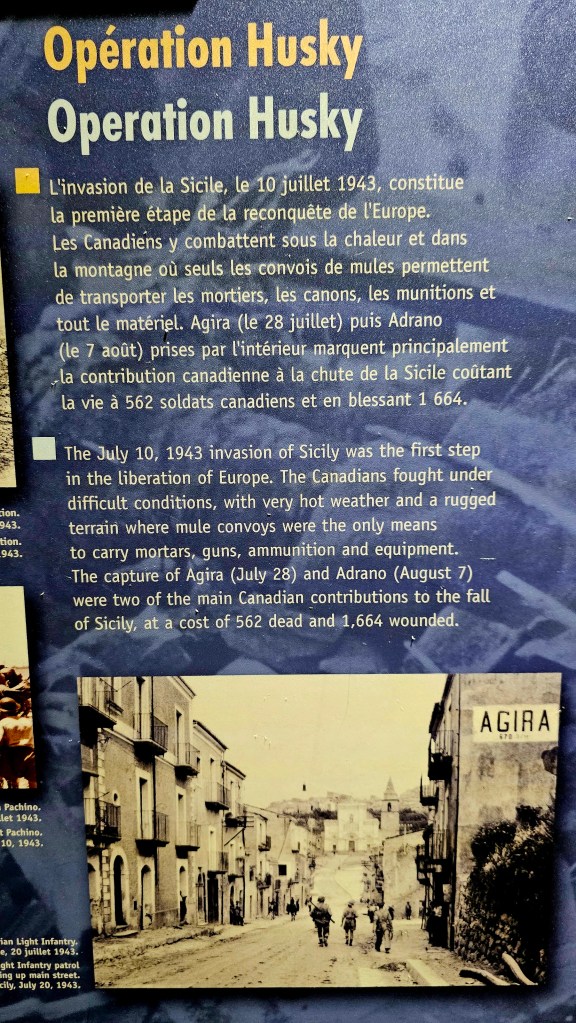

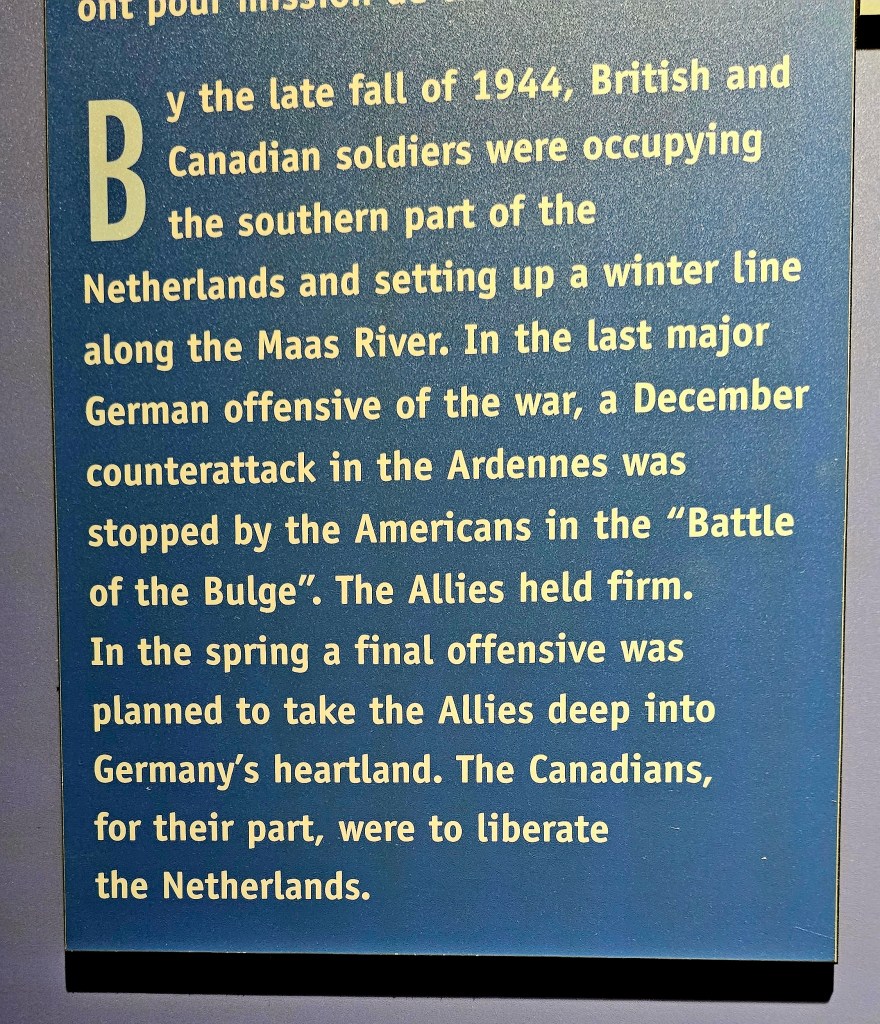

Canadians in the rest of Europe

The history of Canada during World War II begins with the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939. While the Canadian Armed Forces were eventually active in nearly every theatre of war, most combat was centred in Italy, Northwestern Europe, and the North Atlantic.

In all, some 1.1 million Canadians served in the Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Navy, Royal Canadian Air Force, out of a population that as of the 1941 Census had 11,506,655 people, and in forces across the empire, with approximately 42,000 killed and another 55,000 wounded. During the war, Canada was subject to direct attack in the Battle of the St. Lawrence, and in the shelling of a lighthouse at Estevan Point in British Columbia. During the war period, the navy grew from only a few ships in 1939 to over 400 ships, including three aircraft carriers and two cruisers. That maritime effort helped keep the shipping lanes open across the Atlantic throughout the war.

It had been clear that Canada would elect to participate in the war before the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939. Four days after the United Kingdom had declared war on 3 September 1939, Parliament was called in special session and both King and Manion stated their support for Canada following Britain, but did not declare war immediately, partly to show that Canada was joining out of her own initiative and was not obligated to go to war.

Personal note: both my father and my uncle were amongst the first to volunteer for service ( note that all Canadian soldiers overseas were volunteers and very proud of that fact) and amongst the first to be sent oversees. There is a good possibility, given the fact that my father was wounded very early on, that they were amongst the Canadians assigned to the 2nd British Expeditionary Force sent to France and then returned to England for training. My uncle talked about the complete lack of supplies and guns that early in the war.

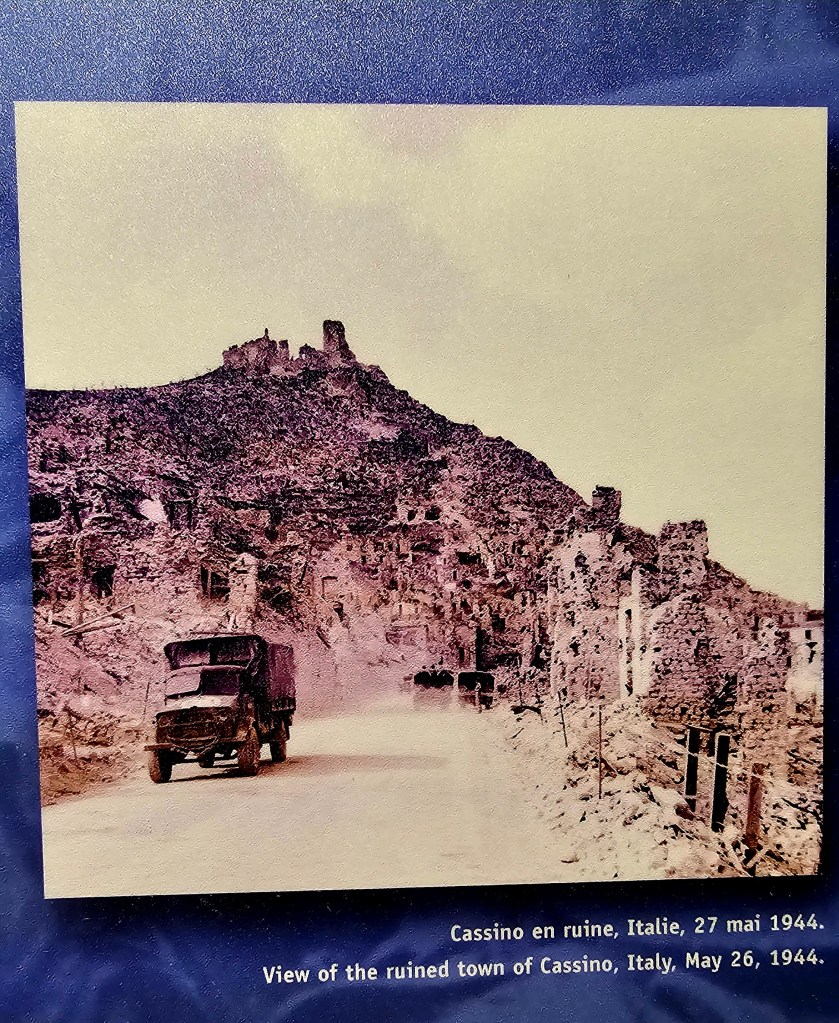

The Canadians in Italy

The Canadians in Italy

I am concentrating on this because my father served in this campaign. As a child he told me stories of occupying farmhouses and having a pet pig (that his troop raised from a piglet and then cried when they finally killed it for food) and finding barrels of good wine. He also saw a lot of fighting which he didn’t talk about terribly much.

The Canadian Cemetary, Beny-sur-Mer

The Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery (French: Cimetière militaire canadien de Bény-sur-Mer) is a burial ground containing predominantly Canadian soldiers killed during the early stages of the Battle of Normandy in the Second World War. It is located in, and named after, Bény-sur-Mer, in the Calvados department, near Caen, in lower Normandy.

The cemetery, designed by P.D. Hepworth, contains 2,048 Second World War burials, the majority Canadian, and 19 of them unidentified.

As is typical of war cemeteries in France, the grounds are landscaped and kept.

Contained within the cemetery is a cross of sacrifice, a monument typical of memorials designed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Bény-sur-Mer was created as a permanent resting place for Canadian soldiers who had been temporarily interred in smaller plots close to where they fell. Some of the Canadian prisoners of war illegally executed at Ardenne Abbey are interred here. It also contains the grave of the Reverend (Honorary Captain) Walter Leslie Brown, chaplain to the 27th Armoured Regiment (Sherbrooke Fusiliers) and the only chaplain killed in cold blood during the Second World War (June 6 to 7, by members of III/25th S.S. Panzer Grenedier Regiment).

As is usual for war cemeteries or monuments, France granted Canada a perpetual concession to the land occupied by the cemetery.

Canadian soldiers killed later, in the Battle of Normandy, are buried south-east of Caen, in the Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery, located in Cintheaux.

You must be logged in to post a comment.